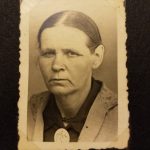

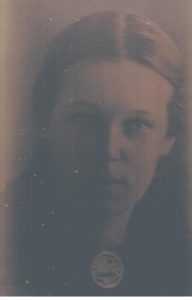

My grandmother, born Elena Haborskaya, to whom Roads is dedicated. It was her voice I heard, throughout my childhood, bearing witness to the events of the momentous Twentieth Century in Russia: born in Tsarist times, her life encompassed the Revolution, the First World War, the Russian Civil War, the Ukrainian famine, the Second World War, and the Nazi occupation of Crimea. Stalwart, self-educated, honest to a fault, she approached life with integrity and faith – qualities that enabled her to face the difficulties of her time, to save herself and those she loved, bring them through the hell of war.

In these photographs, I am struck by the evidence of hardship and hunger etched into the lines of her face, only to be smoothed a few years later when living in relative safety and having regular meals became possible. The constant between them is determination and a seriousness of purpose she would manifest to her dying day.