Here are some discussion points you may want to consider when reading Roads, either alone or in a book group.

What other questions or observations arose in your reading? I’d love to hear your thoughts. Post a comment, if you’re so inclined, or drop me a line.

Reader’s Guide for Roads

Filip thinks of himself as a modern man, the new Soviet citizen, free from the outdated beliefs of Russia’s past. But as he becomes disillusioned with the promise of a bright Socialist world order, where is his place? What does society expect of him, and how does that square with his own understanding, his own ambitions? Where do intellectuals like Filip and Maksim fit into the new scheme of things in their homeland?

Galina’s outlook is apolitical. Steeped as she is in the moral views of her parents, how do her expectations of the future differ from Filip’s? Among her life’s priorities, which ones does she consider most important?

Both Filip and Galina are involved in making art; he is passionate about painting and architecture, she sings. Ilya’s skilled craft work is central to his existence, and sometimes crucial to his survival. Where does each of them place art and beauty in their lives? How does their response compare with Zoya’s love of opera? What effect, if any, do their differing outlooks on art have on their relationships?

What happens when people are unable to freely engage in their religious observances? In a highly structured society, extreme patriotism and political dogma are frequently offered as a substitute for religion to guide daily life and behavior. What are your thoughts on the effectiveness of such change?

Collaboration with the enemy is usually perceived as traitorous and is often punishable by imprisonment, exile, or death. Yet in an area under military occupation, contact with enemy forces is nearly impossible to avoid. Where does survival behavior cross over into disloyalty? How do Borya, Musa, Filip, Anneliese, Dr. Blau exemplify different ways of living with this problem?

Stamp collecting and the game of chess function as a minor motif throughout the story. How does Filip’s preoccupation with his hobbies help define his character? How do these activities relate to his wanderlust, his curiosity, his need for logic? Do they give him any advantage in dealing with the upheavals in his life?

When Hitler’s troops invaded Belorus and Ukraine, they were initially greeted as liberators from Stalin’s oppressive regime. Even though the Nazis’ real intentions became clear almost immediately, many people in the occupied region continued to delude themselves. What examples can you find of naïve ideas among the characters – Filip, Galina, Ksenia, Ilya, Maksim?

When Franz declares his love for Galina, do you believe him? How do his feelings differ from the bond between Filip and Galina, or Ksenia and Ilya? What about Filip and Anneliese?

At several point in the story, the family comes up against evidence of what’s happening to the Jewish people. They are shocked, but remain disengaged. What do you make of their reaction?

Conditions in the German labor camps were marginally better than those endured by prison inmates. Still, the laborers were kept close to starvation, with next to no medical care and no recognition of human dignity. When the camps were disbanded, thousands of people found themselves wandering in a foreign land, looking for a way to survive, knowing that returning home meant certain death. Even in the American DP camps, where conditions were tolerable, there was constant fear of repatriation. How does these people’s refugee plight compare with today’s ongoing crises?

Roads is not a novel about war; it’s an attempt to show how war affects people who are caught up in situations over which they have no control, how they deal with the menace in their everyday lives. Maksim is the only one who witnesses the horrors of combat. Everyone else lives in the wartime environment as civilians, navigating new hardships as they arise. Even Filip and Ilya’s involvement with the ROA can hardly be called military duty. How does this view of the civilian side of the war affect your understanding of Europe and Russia’s ordeal?

The ROA was a desperate attempt to bring about political change in the Soviet Union. Its ragtag army received lukewarm support from Hitler’s commanders, who thought they could use the added manpower in their failing battle against a larger, stronger enemy. Given that the movement was doomed to fail, and would brand any man who participated in it as a counter-revolutionary traitor marked for execution, what function did it serve? Knowing the risks, why did people sign up?

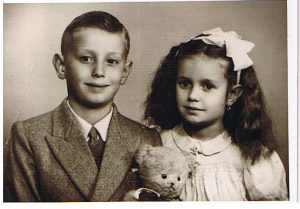

Katya’s birth introduces important change into the family’s life. Her presence affects Galina, Ksenia, Filip, even the unfortunate Marfa; it transforms their status in the world. What kind of life can she expect to have, far from her family’s country of origin, as an immigrant child? What difficulties is she likely to encounter, and what benefits might she receive?

The understanding of home undergoes several shifts in the course of the narrative. Is it still home for Zoya, Vadim, Ksenia, Ilya, when the Tsarist era ends and Bolshevism takes root? Filip comes to embrace home as a state of mind – an idea reinforced by the loss of contact with his family, and the eventual reunion. Is that enough? How does the concept of home change for refugees? For immigrants?