My intrepid father on board the SS Italia, sometime between March tenth and twenty-first, 1956. We sailed from Antwerp, Belgium, where the sun was shining and the sky was clear blue. Rough seas delayed our arrival in New York by one day, though for me, at nine years old, the trip was a continuous adventure, with free movies and board games and good food. Not so for my poor mother, who only saw the dining room on the first day; she spent the rest of the voyage in our cabin, fighting off seasickness.

He taught me chess, on one of those leisurely afternoons. It was a hobby for which he harbored a lifelong passion, playing for years the old-fashioned way – by correspondence with other enthusiasts around the world. Invariably, when people gathered at our home, one corner of the table would be cleared for the chessboard. Amid the music, laughter, conversation, the eating and the drinking, the game would begin, and only end when the last man standing declared his unequivocal victory.

I took no part in those competitions. I was only a middling player, but managed to hold my own until the day my son, aged twelve, roundly defeated me time and again. The new generation had arrived.

From Refugee to Immigrant

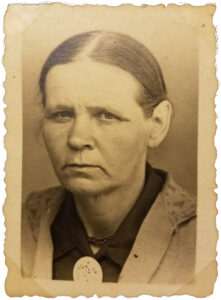

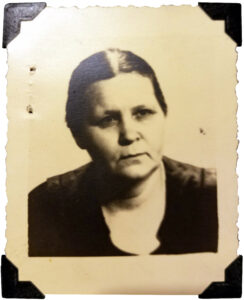

My grandmother, born Elena Haborskaya, to whom Roads is dedicated. It was her voice I heard, throughout my childhood, bearing witness to the events of the momentous Twentieth Century in Russia: born in Tsarist times, her life encompassed the Revolution, the First World War, the Russian Civil War, the Ukrainian famine, the Second World War, and the Nazi occupation of Crimea. Stalwart, self-educated, honest to a fault, she approached life with integrity and faith – qualities that enabled her to face the difficulties of her time, to save herself and those she loved, bring them through the hell of war.

In these photographs, I am struck by the evidence of hardship and hunger etched into the lines of her face, only to be smoothed a few years later when living in relative safety and having regular meals became possible. The constant between them is determination and a seriousness of purpose she would manifest to her dying day.

Leaving for America

Well, here we are. Brussels, 1956. Trunks and cases already on board, documents in order. Friends and well-wishers gathered to see us off, posing for one last time together before the train takes us to the harbor, where we will board the SS Italia for the transatlantic voyage.

I’m the one in the baggy drawers, clutching, most likely, something to read. My brother is on my left, with my mother behind him; next to him is his best Belgian friend (and my first crush), Alain. Behind Alain is my grandmother. My father is second from the end in the back row.

I don’t remember the girl’s name. But I know I desperately wanted a pair of white knee socks just like hers. The reason I couldn’t have them, whatever it was, is lost to history.

Pirog

Chekhov and Gogol called it the glory of Russian cooking.

Chekhov and Gogol called it the glory of Russian cooking.

Pirog, filled with meat for feast days, or cabbage and eggs for everyday consumption, has earned its pride of place among the many great dishes of Russian cuisine. And yet, like the enigma of the Slavic national character, it is a deeply humble dish, rich in its simplicity. Universal. In Roads, it is the one thing Ksenia must make, at any cost, to feed her son, body and soul.

My personal favorite? Potato with sauteed onions and dill. Or maybe sauerkraut cooked with fresh cabbage… It’s almost impossible to choose one when you love them all.

Build it high with chicken filling and it’s called kurnik; salmon layered with rice and mushrooms in a flaky pastry crust makes it kulebyaka. Any variety formed into handy individual shapes becomes pirozhki, without which no traditional Russian buffet table is considered complete. Whatever its name, you can just call it divine.

Perfect picnic food, satisfying snack, a natural accompaniment to soup, pirog, (or its smaller cousin), is as essential to the celebrated zakuski tray as marinated herring, caviar, beet salad, or chilled vodka.

My grandmother, whose baking skills were legendary, could not teach me how to duplicate her creations. She used an old teacup with a broken handle to scoop the flour; everything else – yeast, salt, eggs – was weighed in the palm of her hand or measured by her unfailing accurate eye. Since her passing, I’ve found recipes to outline the proportions. I know what the ingredients are. I can make savory fillings. I spent enough time in her kitchen to remember the technique. What I have yet to learn is how to knead the dough until it “feels right.”

All the more reason to keep trying.

Immigrants

These are immigrant children.

My brother, his favorite (and one and only) fluffy bear, and my four-year-old self, posing for a photograph in a Belgian studio.

What was certainly a luxury was seen as an important way to document our existence, to make a necessary statement: we were here. In the family archives, there are few such records.

Later, with the war receding into memory, my father will own a Brownie camera; there will be snapshots. But for now, the only way to capture our likenesses is to present ourselves, dressed and combed, at the photo studio.

Where is the line between refugee and immigrant? Legal status, yes. Receiving asylum, protection from deportation, permanent residency. Right to work, attend school, receive medical care. The promise of citizenship, not now, but sometime in the future, perhaps. Choosing where to live, once the flight from home is behind you.

There are other, less obvious but no less crucial signs. Asking a gendarme for directions without cringing in fear. Trying out your new language by talking to a neighbor over – why not? – a cup of coffee. Resisting the urge to hoard food, though cleaning your plate is a habit you will never lose as long as you live.

Seventeen

The year is 1943. By now, my mother has completed the eight obligatory grades of school. She opts out of the additional two that would grant her a gymnasium diploma. To what end? Her country is at war. Sitting in a classroom, learning more history and mathematics, seems entirely irrelevant.

Besides, her heart’s desire is to be an actress. She won’t learn that in secondary school, and the art institute is out of the question. She lands a bit part in a local amateur production; loves it. But the time for daydreaming is over. Yalta is overrun by German occupation troops. The business of the day is survival.